Since I started following ALCO 0.00%↑ more than three years ago, Murphy’s law has struck it hard and anything that could go wrong has gone wrong. However, with the stock price falling, margin of safety expanding and the business heading toward an inflection, the setup looks much different now.

As the saying goes: “the safest time to fly is after a crash.” Let’s see whether this also applies to Alico.

But first,

What is Alico?

Alico is Florida’s biggest orange producer. The business model is quite simple. Alico owns around 49000 acres of land which is covered with citrus groves and support facilities for them. These citrus groves are used to produce two varieties of citrus fruit, the first one being Early and Mid-season oranges and the second one being Valencia oranges. Early and Mids are harvested from November through February while summer Valencia oranges are harvested from March through June. These are then sold to Tropicana, who accounts for 80%+ of revenue, as well as to a few smaller players. All of them use oranges to make, you guessed it, orange juice.

Tropicana makes money by selling liters of juice rather than oranges, hence, pricing in this industry is based on "per pound solids." Which is a fancy name for the amount of sugar and acids contained in a single box of oranges.

This is where the story gets interesting. Alico has two multi-year contracts with Tropicana in place, and the first one was just renewed about a month ago.

The contract is effective from June 2024 through July 2027 and allows Alico to sell the oranges grown on 65% of currently planted acres at prices per pound solids that are approximately 33% to 50% higher than the average price for all the citrus sold to Tropicana last season. ~June 10, 2024

This means that for the next three harvests, Alico has locked in substantially higher pricing for two-thirds of its production capacity. The second contract with Tropicana expires in August 2025 and I expect them to agree on similar or better conditions, allowing Alico to charge record prices for as many pound solids as they can produce.

However, if Economics 101 taught us anything, it is that the price is only one part of the equation, with volumes being the other.

Orange Is the New Green

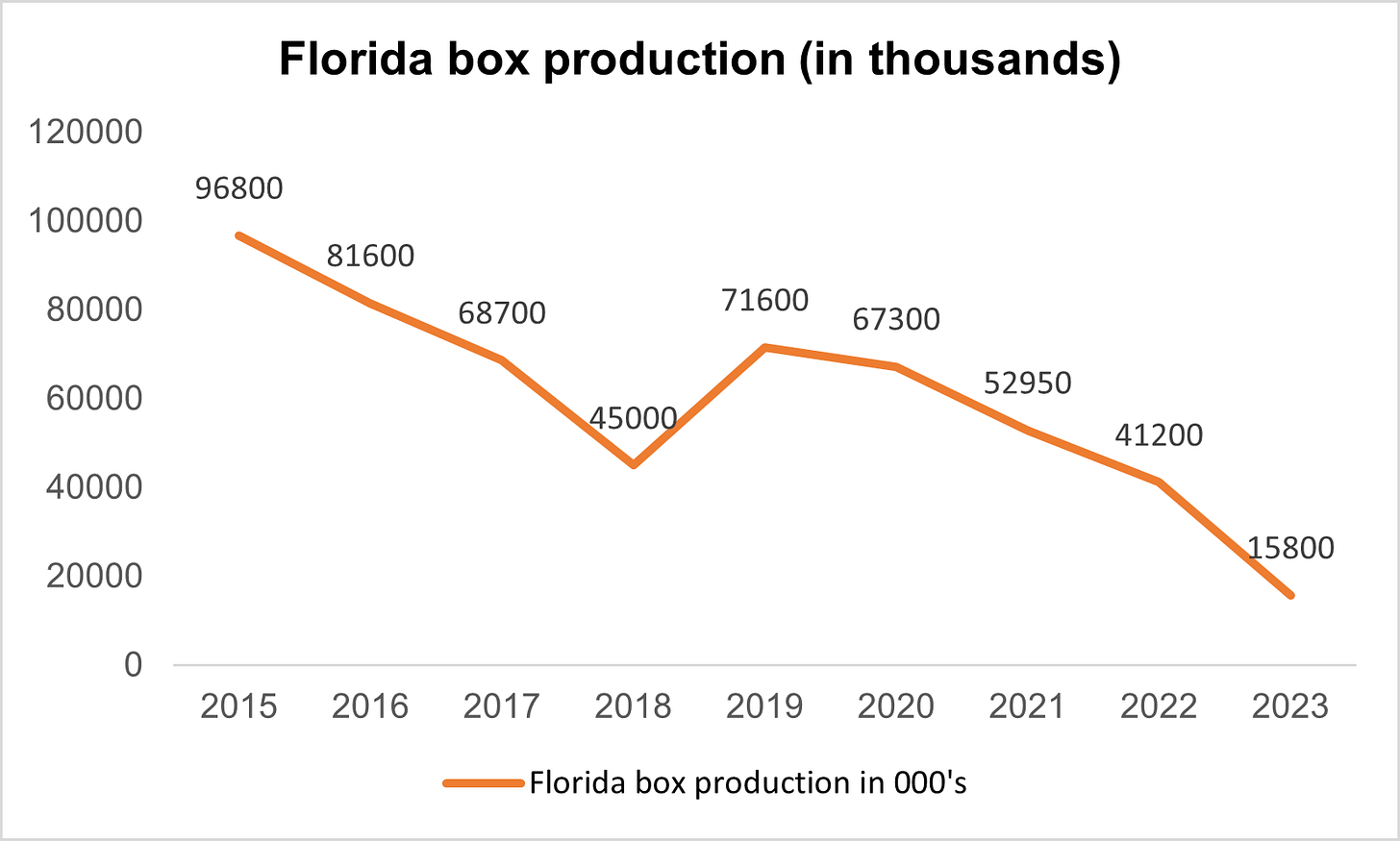

Unfortunately, volumes in the Florida citrus industry have been dropping all throughout the twenty-first century. For example, Florida harvested nearly 100M boxes of citrus less than a decade ago, compared to only 15.8M in the previous harvest. An 80%+ decline.

The primary explanation for this is something called Huanglongbing (HLB). HLB, often known as citrus greening, is a bacterial disease carried by insects. It is severe, reduces tree productivity, and, as of yet, there is no cure. While it does not affect people, it has ruined citrus groves worldwide, particularly in Florida, since its arrival 21 years ago. The disease caused the trees to produce green and bitter oranges, making them unfit for juice.

As oranges lose their quality, they drop sooner and shrink in size, resulting in lower productivity/yield per acre. To prevent that or slow the process down, you must spray and fertilize more than usual. Also, because infected trees typically die much faster than healthy ones, you need to replant acreage at a very fast clip if you wish to maintain previous production levels.

Pretty concerning, right?

It sure is. However, explaining the recent drop in volumes only because of citrus greening would be missing the big picture.

Hurricane Ian

As I mentioned in the opening, apart from citrus greening, two other factors have led output to seem as awful as it does right now.

First, in January 2022, Alico was hit by an intense freeze that had not occurred in Florida in over 20 years, resulting in a higher rate of fruit drop, particularly in Valencias, than in prior years and preventing oranges from maturing to their full size. If that wasn’t enough, later that year, Hurricane Ian, with its 150 mph winds, hit and severely wrecked Florida’s agriculture, causing an additional significant drop in fruit and affecting the majority of Alico’s groves.

In reaction to this calamity, Alico slashed its dividend by 90%, accelerated the harvesting of oranges to minimize further fruit drop, and increased capex to return to normal production levels. It also forecasted substantial operating losses and estimated that “it may take up to two full seasons or more for the groves to recover.” This sent the stock down 40% in the last two years.

Fortunately, unlike citrus greening, all these problems are solvable and only temporary.

Although trees are definitely taking longer to recover than they did after Hurricane Irma, the management has repeatedly stated, that there’s no long-term damage to the trees and that nearly all their citrus survived the catastrophe. Moreover, Alico has crop insurance on all of their acres and has received more than 28M in insurance proceeds in the meantime, compensating for part of the losses.

We still don’t know whether Alico will be eligible (and how much) to receive “federal relief” grants for Hurricane Ian. After the most recent Hurricane Irma, which struck Florida in 2017, Alico received 25.6M. And Irma did less harm than Ian.

Unfortunately, nearly two years have passed since Hurricane Ian hit there has been no word from the government. Because time is not our friend here, it is likely that the longer it takes them, the less the payback or the slimmer the likelihood that Alico will receive anything.

Because I don’t understand the legislation or the relief mechanism, grants are not something I’d include in my valuation or bet on. Nonetheless, I felt it was worth highlighting here since if this grant is comparable to the one received for Hurricane Irma (25 million+), it would yield Alico 13% on its current 195M market cap.

Also, if you check the timeline of Hurricane Irma's federal relief, you’ll notice that Alico only began receiving those grants in FY 2019.

Now that I’ve outlined the steady long-term decline caused by citrus greening, as well as the temporary declines caused by freeze and hurricanes, it’s finally time to outline the positives and what leads me to believe that current operating losses are a one-off, and we’re on our way to higher prices, higher volumes, and a better-positioned Alico within the Florida citrus industry.

Capital Cycle

Although citrus greening affects everyone, it doesn’t affect everyone the same. After reading some expert calls, one thing stood out. Economy of scale is important. And Alico has the scale.

“We believe that we have the most productive citrus groves in Florida." ~Q1 2023

Scale is important for several reasons. Aside from the obvious savings from purchasing larger quantities of fertilizers and sprays, scale also allows you to tackle citrus greening more effectively. This disease mostly affects trees at the edges, making smaller blocks of citrus more vulnerable due to, of course, more edges. Larger, contiguous groves with fewer edges have reduced infection rates and improved quality and productivity. And a better chance to survive and thrive as the industry consolidates.

The best example of this is Alico’s Joshua Grove. It spans 22,389 acres and accounts for 45% of the company’s overall land. Additionally, the five largest groves account for more than 70% of Alico’s total acreage.

Moreover, if constant battles with citrus greening weren’t enough, two hurricanes did the trick and caused many of the small growers to give up fighting and go out of business. Larger players, such as Alico, can take advantage of this position by adding “abandoned” neighboring acreage to their existing groves.

One example of this is Alico’s purchase of Alexandre Grove for a meager 5K per acre, compared to the "fair" value that probably exceeds 8K per acre (but more on acre prices later).

“On October 30, 2020, we purchased approximately 3,280 gross acres located in Hendry County for a purchase price of $18,230 thousand. This acquisition allowed us to add additional scale to our then approximately 46,000 gross acres of citrus properties. Strategically, with these acquired groves neighboring existing Alico groves, we believe that this acquisition will help us with our operation designed to be a low-cost, high-producing citrus grower.”

“And we have access to capital as a public company that, honestly, our competitors can’t really kind of measure up against. So in the event that there are willing sellers at reasonable prices, Alico should be the first call to basically strike a deal.” ~Q4 2021

This trend of the big getting bigger and better is particularly evident in the last few years, with Alico declining slower than competition and taking market share.

This trend of Alico taking market share from its Florida-based competitors is one that I believe will not only continue but even accelerate. Here's why:

Plants vs. Zombies

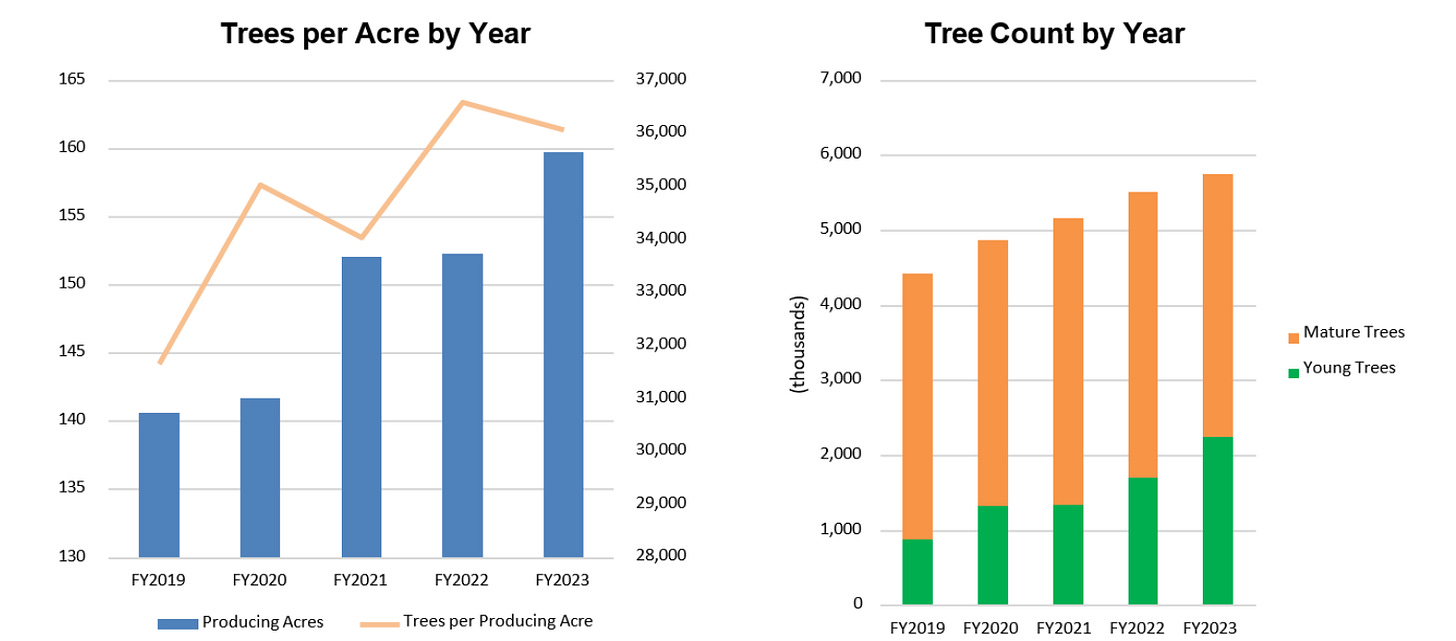

Along with the recently signed contract with Tropicana, these two graphs are perhaps the most important things to consider for this thesis. Examine them closely.

Now that you have, we can finally get back to Economics 101 and my expectations for future volumes.

Alico began to accelerate its tree plantings in 2017. Since then, they have planted 2.2 million new trees, bringing the total to more than 5.5 million trees as of Q1 2024. As a result, both producing acres and trees per acre have increased steadily over the years.

The useful life of a citrus tree, based on Alico’s annual report, is 25 years. If you ask around, that 25-year figure is more than conservative. So let’s do a rough “maintenance” calculation:

Alico had no more than 4 million trees planted in 2017, which indicates that, based on the 25-year useful life, Alico needed to plant around 160K new trees per year to sustain previous levels of output. So, between 2017 and 2023, Alico had to plant around 1.1 million new trees only to maintain historical levels of production. And, of the 2.2 million total trees planted, approximately half, or 1.1 million, were net new trees that will increase output on existing acres. This represents at least a 27% increase in total output potential compared to 2017.

New trees typically require 4-5 years to bear fruit and approximately 8 years to mature. This means that all these new trees are not yet reflected in the current financials. However, in the coming seasons, most of them will either „peak” or mature enough to produce meaningful amounts of oranges.

Management believes that this tree-planting strategy will allow them to recover to a production level of 10 million boxes. The number last achieved in FY 2015.

With lower costs than in 2015 and better pricing, if remotely close, Alico is on track for its best year on record.

So, if you believe devastating hurricanes and freezes are not going to repeat year in year out, or that citrus greening is not going to rapidly accelerate after more than 20 years of its presence in Florida, Alico is entering an environment of both high prices and high production. A double whammy.

Moreover, what if the citrus greening risk can do a 180 and turn into an opportunity in the future?

ƃuᴉuǝǝɹƃ snɹʇᴉƆ

Earlier, I noted that Alico is Florida's lowest-cost producer, but I neglected to mention that NFC (not from concentrate orange juice) made from Florida oranges competes with NFC juice in Brazil.

Historically, Brazil has been far more successful (or lucky) in controlling citrus greening, owing to lower spread but also to the fact that there were so many groves that it made sense to literally burn down sick trees and groves or grow them so far apart that insects couldn't reach them.

Furthermore, lower labor costs enabled it to take market share from other citrus regions, such as Florida, and corner over two-thirds of global orange juice production.

Fortunately (for Florida), the citrus greening problem in Brazil has increased exponentially in recent years than it has in the past. And Mr. Kiernan thinks that in terms of citrus greening, Brazil is currently where Florida was 20 years ago.

Moreover, if the certainty around pricing isn’t enough, citrus greening accelerating in Brazil should ensure that Florida and Alico remain competitive for the foreseeable future and prices stay elevated.

Another scenario that I am not betting on but that is still worth mentioning because it would probably make this a home-run investment is the OTC (Oxytetracycline) treatment.

It is a therapy for trees, developed to mitigate some of the impacts citrus greening has on trees. Alico began testing it in 2022 and treated 35% of trees with it in 2023.

Overall, the results appear to be slightly positive in terms of increased orange production but have yet to bear fruit (pun intended) in terms of quality. The results clearly met management’s expectations, since they plan to double the amount of trees treated during the current harvest season.

Supposedly, benefits from OTC can kick in even after year 1, so I’m excited to follow how the situation evolves and read the entire Alico’s quantitative evaluation of the therapy after the current harvest season.

Now that I’ve outlined the main risk of citrus greening and my expectations for high volumes + high prices, let’s see how it will affect Alico’s profitability.

Cost structure

As is the case with most cyclical companies selling commodity products, Alico’s expense base is mostly fixed, causing a large operating leverage effect on the business in good years and likely cash bleed in bad ones.

Costs can be split into three categories, the first being COGS, or the cost of maintaining citrus groves, which, by 10K’s own words, “does not vary in relation to production.” The second one is harvesting & hauling, which represent the costs of bringing citrus products to processors and vary based on the number of boxes produced. And the third one, G&A, is also mostly fixed.

It should be highlighted that current management has done a successful “restructuring” job since 2016, cutting 20 million+ in costs to enhance margins and hence the ROIC.

Except for the 2021/2022 harvest season, when fertilizer costs skyrocketed and Alico experienced significant increases in basically every cost imaginable (herbicide, labor, and fuel), the cost benefits are pretty obvious, and I think can be best seen by looking at a trend in underlying (excluding insurance proceeds, federal relief, sales of property, third-party grove management and fresh fruit sales) citrus margin for the years where Alico’s business was operating in a “good” environment and recording revenue growth.

With costs down, the pre-hurricane Irma harvest (2019) recorded 21% underlying EBIT margins, up from the 13% level in 2016 when Alico began implementing cost cuts.

With over a million young trees maturing, elder ones recovering from the hurricane, and higher prices locked in, I expect even greater operating leverage to take place going forward.

Underlying citrus P&L

Here's how I see underlying citrus P&L changing in the coming years:

7-10 million boxes harvested

With our approximately 1.5 million trees planted over the last four years, we believe we have the potential in the long-term to return to the Company's annual citrus production level of approximately 10 million boxes and that level was last experienced by our company in fiscal 2015. ~Q2 2021

5-6 pound solids per box

10-yr median of 5.7

35-60 million of total pound solids produced are calculated as boxed harvested x pound solids per box

average price per pound solids of 3.5$-4$

Taking into account the recently negotiated contract with Tropicana and the second large contract coming due in Aug 2025

revenue is calculated as total pound solids x price per pound solids

COGS of 60 - 70 million

Labor and fuel remain critical resources for us and although we utilize both as efficiently as possible in our daily operations, inflation over the past few years has increased the base level of those operating expenses ~Q3 2023

Harvesting & Hauling costs of 23-27 million based on 2.7-3.3 h&h unit costs per box

10-yr median of 2.8 h&h costs per box

10-12 million in G&A costs

3.5 million in net interest expense

70M out of 84M of total debt is interest only, fixed at 3.85%, with a balloon payment due on November 1, 2029

corporate tax rate of 21%

I believe base-case numbers are conservative and that the bull case is more plausible than the bear scenario. Moreover, I’m glad that after an awful two years of Alico draining cash at a rapid pace, it won't take much for them to turn profitable again.

Also, none of my rough estimates don't include the possible benefits of OTC treatment, federal relief grants, or tax shield gained from losses incurred over the previous two years. Alico's income from the fresh fruit sales, as well as the large fees coming from the grove management services Alico provides, are also not included.

On October 30, 2023, we entered into a Citrus Grove Management Agreement (the “Grove Owners Agreement”) with an unaffiliated group of third parties to provide citrus grove caretaking and harvest and haul management services for approximately 3,300 acres owned by such third parties. Under the terms of the Grove Owners Agreement, we are reimbursed by the third parties for all costs incurred related to providing these services and receive a management fee based on acres covered under this agreement.

As can be seen, with the majority of the cost base being fixed and pricing locked in, the most critical item to consider for future profitability is the total pound solids sold.

I usually avoid seasonal businesses, such as citrus producers. Aside from its low-cost advantage, Alico is a price-taker, susceptible to extreme weather disasters, and subject to wide fluctuations in pricing and volumes year after year. However, I still find the forward valuation of ~3.5x P/E (probably 2 harvests out) far too cheap, and am willing to wait until I see the light at the end of the tunnel that’s about to come with strong volumes and pricing.

Disregarding the business solely because it’s cyclical or lacks a “moat” is IMO missing the forest for the trees (okay, enough with puns).

Moreover, it’s much easier to sleep peacefully at night while you’re waiting for bears, who are extrapolating a permanently negative environment, to come out of the closet when you have significant downside protection on your side.

And Alico’s downside protection makes potential errors in my projections almost irrelevant and is so significant that I like to refer to it as:

Upside protection

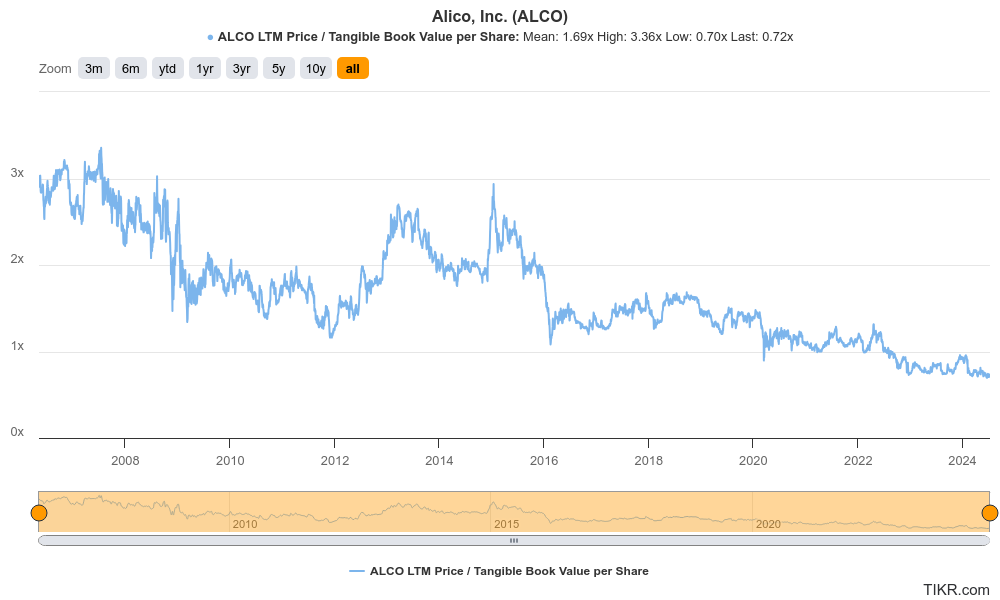

The first and most obvious downside protection is the good ol’ P / tangible book. It currently sits at 0.72x, reaching the lowest point in Alico’s history.

Of course, this tangible book is prone to accounting "errors." 49,000 acres of citrus land comprise most of Alico's assets, and their value hasn't changed on the balance sheet in far too long.

To properly understand the “real” downside protection, it would be wise to look beyond accounting to see if PP&E and land value accurately reflect how much Alico is worth today.

Adjusting the book is often hard, but luckily, with a little digging, I found data on verified Florida land sales by property type.

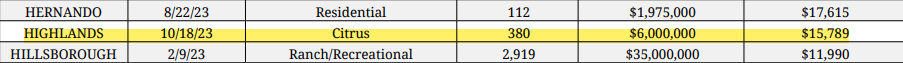

According to Saunders Ralston Dantzler’s report, in 2023, Florida citrus landowners sold 15,699 acres of land at an average price of $9284 per gross acre. Although the total volume of transactions dropped by 69% to 40 compared to 2022, the average price per gross acre grew by 7% compared to 2022, which had already increased by 18% from 2021. Demonstrating the resilience of Florida’s RE market and what a little inflation can do to land values.

Alico's latest sale confirms this land valuation.

“In April 2024, we entered into an agreement to sell another approximately 780 acres of land at the 2x6 grove to a third party for approximately $7 million or $9,000 per acre, and that includes an option to purchase another 680 acres within 10 months from the closing date of the sale at the same price per acre, but Alico will continue to grow citrus on those 680 acres for the next harvest season.

This new transaction, which is expected to close by the end of July 2024, illustrates our strategy of monetizing underperforming citrus groves on a case-by-case basis to redeploy capital to generate better returns for our shareholders.” Q2 2024

The key word here is “underperforming.”

If we apply the same 9,284 per acre math to Alico's 48,949 acres of land. We can adjust the land value to 454M, which is substantially higher than the 113M stated on the balance sheet.

However, most of Alico’s PP&E (aside from the land) is made up of assets that add or give value to that land (citrus trees, a tree nursery, equipment, and other facilities). So to be super conservative, I believe it’s prudent to compare 454M to the full 360M PP&E amount shown on the balance sheet. Still a large increase.

Before we compare the adjusted book to the current market cap. There’s something else worth addressing.

In addition to the citrus business, Alico has recently been active in the cattle and ranch business. Aside from the citrus business, in the recent past, Alico has been involved in the cattle and ranch business as well. Beginning in 2018, management indicated that they no longer wanted to be involved in the Alico Ranch business since it didn’t offer them adequate returns. They began selling the 69,000 acres of land they owned, selling everything except 5625 acres.

Because of its huuuuge size, I believe the most recent sale of 17,229 acres to the state of Florida for $4350 per acre should be the absolute floor for pricing of the remaining acreage in Alico’s ownership.

I expect management to sell the remaining ranch land rather quickly because most of it is concentrated in a single 4022-acre large plot, and the CEO is incentivized based on a percentage of net sales proceeds from the approved sales of Alico ranch acreage (percentage ranging between 0.6% and 1.1% based on the gross sales price per acre in each respective sale).

Private transactions for ranch & recreational land in Florida further support the $4000-$5,000 per acre price point:

Now we can finally do our “upside protection” calculation.

Although I don’t expect Alico to sell the majority of its citrus acreage, I like the fact that this discount is so large that even if you imagine a worst-case scenario fire sale, you still don’t stand to lose money. Or even make some. And that is exactly what I look for when buying a cyclical business near its cycle trough.

Aside from the downside protection, some of Alico’s land also offers:

Land optionality

Given that the CEO has repeatedly stated that he’s committed to citrus in the long run, I believe valuing Alico based on citrus profitability rather than land value is the “way to go” for the time being.

However, I don’t think Mr. Kiernan is “married” to the land or its citrus. On the contrary, he has shown a determination to prioritize ROIC maximization above all else. Even if it meant ditching citrus.

And it appears that the decision to ditch part of the citrus business became easier in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian:

Last year, after evaluating the direct hit it took from Hurricane Ian in 2022, we made a difficult decision to transition our TRB Grove in Charlotte County from a proprietary citrus operation to a mix of third-party mining, vegetable and fruit crop leasing activities. This year, we evaluated another struggling grove and have decided to also move beyond citrus there to realize its highest and best use. In 2022, we entered into a purchase option agreement with a third-party E.R. Jahna Industries for the sale of approximately 899 acres of land at a price of approximately $11,500 per acre on our 2x6 grove located in Hendry County, Florida, which expires in January of 2025. It is expected that this option agreement will be exercised by the end of December 2024. It is understood that Jahna plans to conduct sand mining operations on the land once regulatory approval has been obtained. And Alico will have the right to lease back most of these acres, including 340 net citrus acres for de minimis lease payments. – Q2 2024

Whether it is selling the land for alternative agriculture, mining, or renewable energy, management has a variety of options for realizing the "best use" for every acre they hold, narrowing the discount to fair market value.

The one alternate use I’m most bullish on is the potential of selling the land to someone with residential or commercial RE development ambitions.

In fact, on May 28th, Alico announced that Mitch Hutchcraft joined the company in a newly created position as Executive Vice President of Real Estate, with the priority of accelerating the entitlement process for Corkscrew Grove located near Fort Myers, which began in 2023.

Given that Fort Myers is one of, if not the fastest-growing places in the US, that 4500-acre grove is likely the most valuable piece of land Alico owns. Once the entitlement process is completed, Alico should be able to sell it for at least 20K dollars per acre, and most likely considerably more.

To back that claim, consider the following data on Florida land transactions that have been repurposed and rezoned from citrus to another use.

As shown in the chart, there were nine transactions in 2023, with an average price of $22,000 per acre, all of which were in arguably less desirable locations than Corkscrew.

I had a call with a fund (that I won’t name) that owns a substantial position in Alico and has spent time on the ground, doing scuttlebutt and meeting with the CEO and the new VP of RE. And they believe that if repurposed, Corkscrew might be worth more than $30,000 per acre.

When will it be repurposed? Idk When will it be sold? Idk

But I do know, that it’s definitely worth multiples of what the current market cap implies for pricing per acre.

For example, suppose these 4500 acres were indeed sold at a 20K–30K per acre price point a few years from now. Corkscrew Grove would yield Alico 46-70% of the current market cap, and 33-50% of its current EV.

For a property that accounts for less than 10% of Alico’s total gross acreage, this is pretty neat.

By playing around with transaction data, Google Maps, and Alico’s interactive map, I tried to identify other groves that have the potential to be repositioned for residential/commercial, or industrial purposes one day.

I concluded that no more than around a quarter of Alico’s acreage has the potential to be rezoned at some point (including Corkscrew). While management believes that amount is closer to half of the total acreage and aims to reposition it primarily for residential RE use.

I think 1224 acres located in Highlands County are worth roughly 15K per acre, whereas 6869 acres in Polk County would sell for 20K–25K per acre on average if repurposed.

Here is the last two years' worth of transaction data for transitional citrus land in these counties.

I am aware that entitlement processes are lengthy and uncertain, but if there’s one place in the US where you will most likely get paid for waiting, it is Florida.

“Florida is once again poised to experience significant population growth as well as an increase in transitional land. Factors contributing to the state's allure include its climate, moderate cost of living, active lifestyle, amenities, no personal income tax, favorable business environment, and ample job opportunities. Florida stands out as one of the top markets in the nation in many metrics. Consequently, the value of transitional land has steadily risen to meet the demands of this growth.” ~ Saunders Ralston Dantzler Real Estate, Lay of the Land, Florida 2023.

With the confirmed margin of safety, while waiting for confirmed business inflection, there’s only one factor that could potentially mess this thesis up.

Management

If you ever decide to listen to Alico's conference calls, you'll notice that the CEO, John Kiernan, is very promotional. Most of the time, I run away from CEOs who are this salesy. However, over the call, he doesn't seem that way. And given his background in investment banking for 12 years or as a VP of IR, it is only logical that he would be more promotional than your average CEO.

His promotional red flags become less important when you consider his shareholder-friendly track record.

opportune sales of Alico ranch and underperforming citrus land

paid down 120M+ of mostly unattractive variable debt since 2015, significantly deleveraging the balance sheet

paid consistent dividends which were increased during good harvest seasons

returned capital via buybacks and a large tender offer in 2018 but a higher stock price than it is today

significantly reduced costs with the Alico 2.0 program

Alico has a lengthy history of self-serving or incompetent CEOs, so I’m glad that with Mr. Kiernan, shareholders have finally "found" someone who is business-savvy and, more importantly, good at capital allocation.

And while his insider ownership is meaningless, there are multiple incentives in place to guide his decisions going forward.

Alico’s management takes lower base salaries but higher bonuses in stock than the industry or than your average company. This compensation is based on annual adjusted EBITDA, the six-year average ROIC, and the stock price performance (if it surpasses 35$-50$ a share).

I also noticed that the CEO's Change of Control clause was inserted for the first time into the 2023 proxy statement.

For example, if Alico is acquired for more than 55$ per share, Mr. Kiernan stands to gain 1.25% of the sale or more than 5 million dollars. So, if volumes don't recover as fast as he expects, he has a strong motive to sell the company. And I’d be quite pleased if he manages to pull this off.

PS Insiders own 8% of Alico

All in all, I like what Kiernan has accomplished since joining the company in 2015. He knows his stuff and I had a pleasant time talking with him today.

Not to prolong this write-up any further, I’ll leave you with a short risk section

What could go wrong?

Although land value and optionality take care of most, if not all, of the scenarios in which you stand to lose money on this investment, there are some risks that could turn the risk-reward ratio from great to only average.

citrus greening disease in Florida is accelerating, making volumes permanently lower and putting pressure on land values over medium- or long-term

Fortunately, infection rates cannot mathematically increase because 100% of trees in Florida are already infected. However, if this one materializes and trees in Florida get exponentially more tired or sicker, it will most likely make Alico a value trap.

Tropicana dropping Alico

Although PepsiCo just sold its majority stake in Tropicana to a French PE firm, PAI partners, the likelihood of this risk occurring is IMO close to 0. Alico has been Tropicana’s primary supplier for decades, and recent multi-year contracts at record-high prices confirm the mutual respect and strength of this relationship. Especially now, given that the world appears to be heading towards de-globalization and with shipping costs going up, I doubt Tropicana can “afford” to risk it all with Brazil or Mexico. The occurrence of this risk would be catastrophic in the short term until (or if) replacement buyers are found.

pricing deteriorating below the minimum floor prices signed in contracts

Even though pricing in this largest contract, as previously said, should remain stable within the 3.5-$4 per pound solid range, there’s a chance that prices will surprise to the downside or upside. According to this agreement with Tropicana, if the market price falls below the floor prices or exceeds the ceiling prices, then 50% of the shortfall or excess needs to be deducted from the floor price or added to the ceiling price. I don’t see demand outstripping supply any time soon, but I guess if there’s a scenario of significant production rebound internationally and in Florida, it would put some pressure on the 3.5-dollar-per-pound solid minimum that I am expecting.

huge spike in COGS, particularly fertilizer and chemicals, over which they have no control

This should keep COGS at around 70M+ for some time.

another deadly hurricane hitting Florida, decimating crop and increasing Alico’s future insurance bills

That’s all from me, dear investors. I appreciate you taking the time to read this!

disc: I hold a 12% position in ALCO 0.00%↑ at a slightly lower price than it is now.

This is NOT investment advice. All content on this website is for entertainment, informational, and educational purposes only and should not be considered to be advice of any nature. Due your own due diligence.

Amazing write up!

My only comment is that I personally think the risk associated with tropicana being aquired is potentially significant. It wouldn't be the first time a PE firm has destroyed historic B2b relationships to shave margins fractionally higher. As tropicanna accounts for most of their revenue, the future contract renewals may not be so positive as the recent.

Perhaps bad news pertaining to the orange farming business is good news for the stock? It will come under more pressure to sell land for housing development, etc?